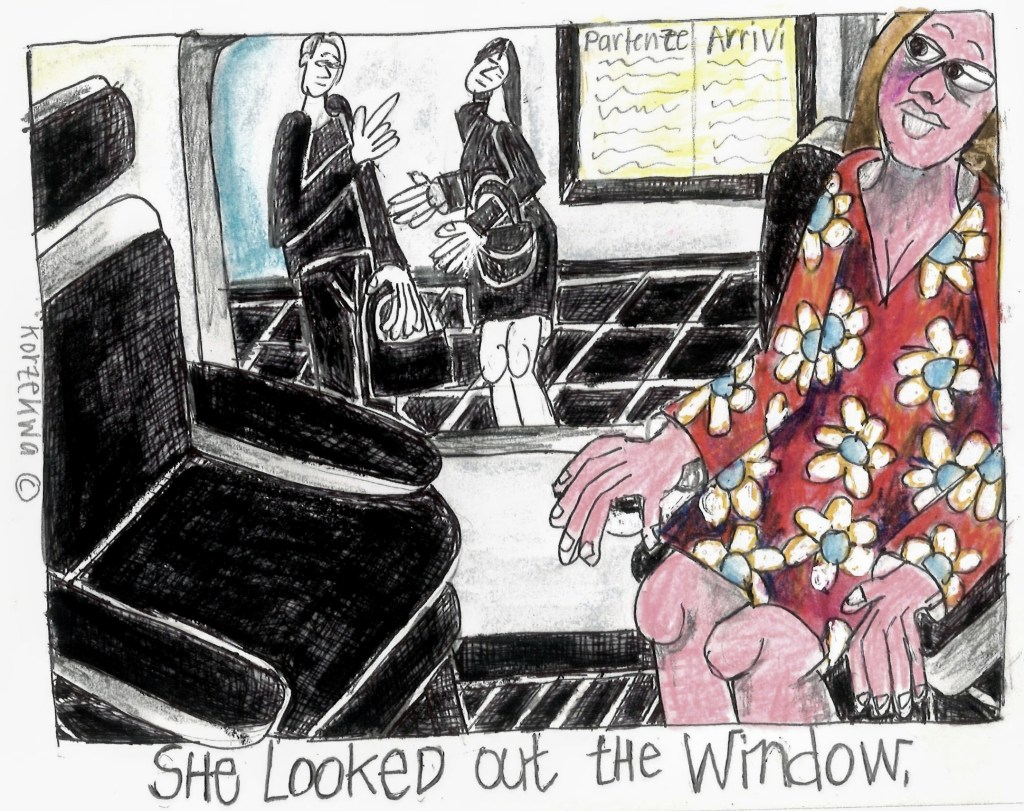

The summer of 1993, I was in Venice for the Biennale. For the train ride back to Tuscany, I’d been given a first-class ticket and eagerly went to my compartment. There was still some time before departure so I sat and looked out the window. On the platform in front of me, I recognized Pietro Citati (1930-2022), a writer best known for his biographies and literary criticism. He’d also written a short memoir on his friendship of 30 years with Italo Calvino

I was rather surprised when Citati entered my compartment. He politely said “Buongiorno” before heading towards the window seat. Once there, he pulled out a notebook and started writing non-stop.

No one else was in the compartment so discreetly observing him was a problem. But he didn’t even notice me (or so I thought) as he was fully immersed in his writing. Every so often he would look up and stare into space. Then, ZAP! The muse was back and he’d quickly start writing again. Meanwhile, I pretended to read as I simultaneously pretended not to look at him. But it was a long ride and thus difficult to ignore one another.

Maybe I was the one who tried initiating a conversation with some comment like how intriguing it was to watch him write with such intensity. Citati’s response was that he’d been afraid of stepping on my feet when passing in front of me to get to his seat.

Citati talked but with a strong sense of reserve (he was Florentine). However, he did reveal, without ever saying his name, that he lived at Roccamare, was a writer, wrote every morning and walked every afternoon (or was it the other way around?). The area where he lived was near the sea and full of umbrella pines.

When we arrived at the destination, we politely said goodbye and then went our own ways.

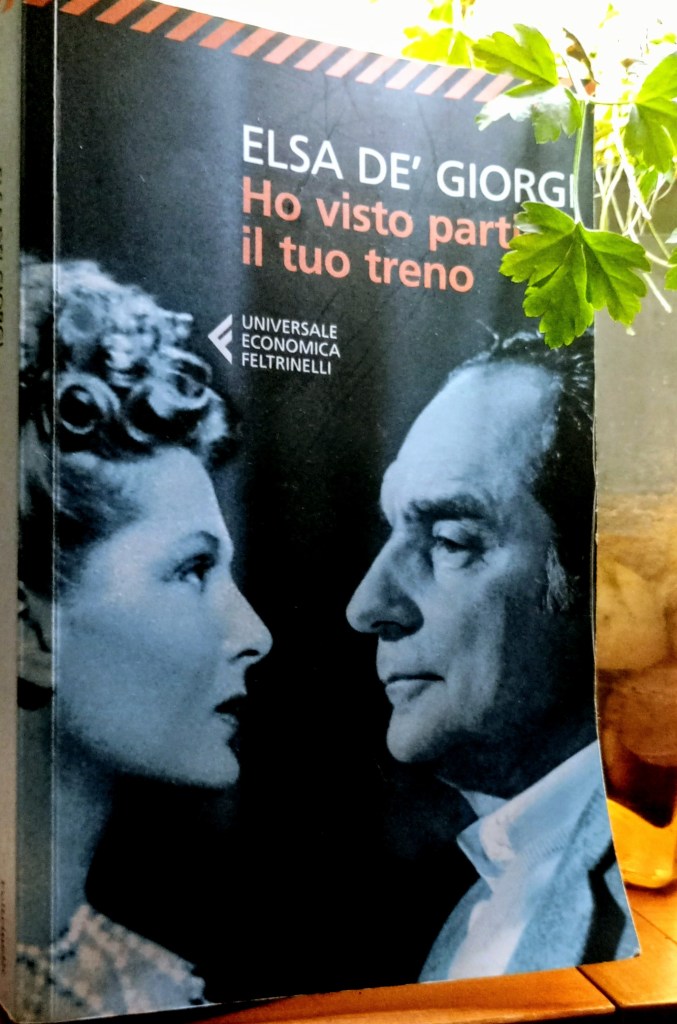

Recently I read Elsa de’ Giorgi’s “Ho visto partire il tuo treno” (“I saw your train leave”). Elsa and Italo Calvino were lovers for a while and had many friends in common. Elsa mentions Citati various times. She describes him as having “occhi limpidi pieni di pensiero” (“clear eyes full of thought”).

Elsa, a writer herself, enjoyed organizing encounters at her home. She speaks of the time when Carlo Emilo Gadda came to stay in Rome. Gadda was a well-respected writer from Milano and the writers in Rome were behaving like groupies. Elsa says Citati encouraged her to take good care of Gadda and to make sure his needs were met.

Gadda and Citati became very good friends and for years corresponded. Gadda’s letters to Citati (1957-1969) were published as “Un gomitolo di concause” (“a tangle of contributing causes”). It must have been a very special relationship as, a few days before dying, Gadda asked Citati to read the 8th chapter of “Promessi sposi” to him. Bittersweet.

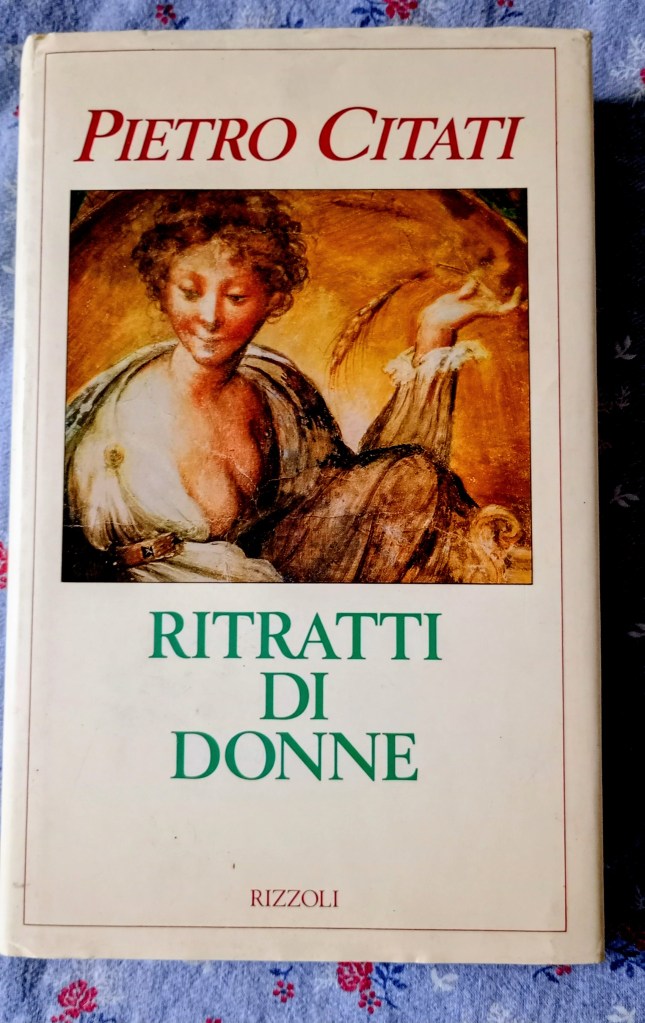

Elsa’s description of Citati provoked my curiosity. I found my copy of Citati’s “Ritratti di donne” (portraits of women)(1992) and leafed through it until I landed on the poetessa Cristina Campo (1923-1977).

Citati immediately complains about the woman on the bookcover of Cristina’s “Gli imperdonabili” having nothing to do with Cristina who was more like Hugo van der Goes “The Portinari Triptych” at the Uffizi. Mary is in the center of the triptych dressed in black with long hair floating on her shoulders. She’s kneeling in front of God with her hands folded. Citati also likens Cristina’s face to that of a 13th Cen Tuscan statue (you’d think he’d had a crush on her). Cristina, continues Citati, always emanated a sharp icy Florentine air, illuminated by a perpetually white light.

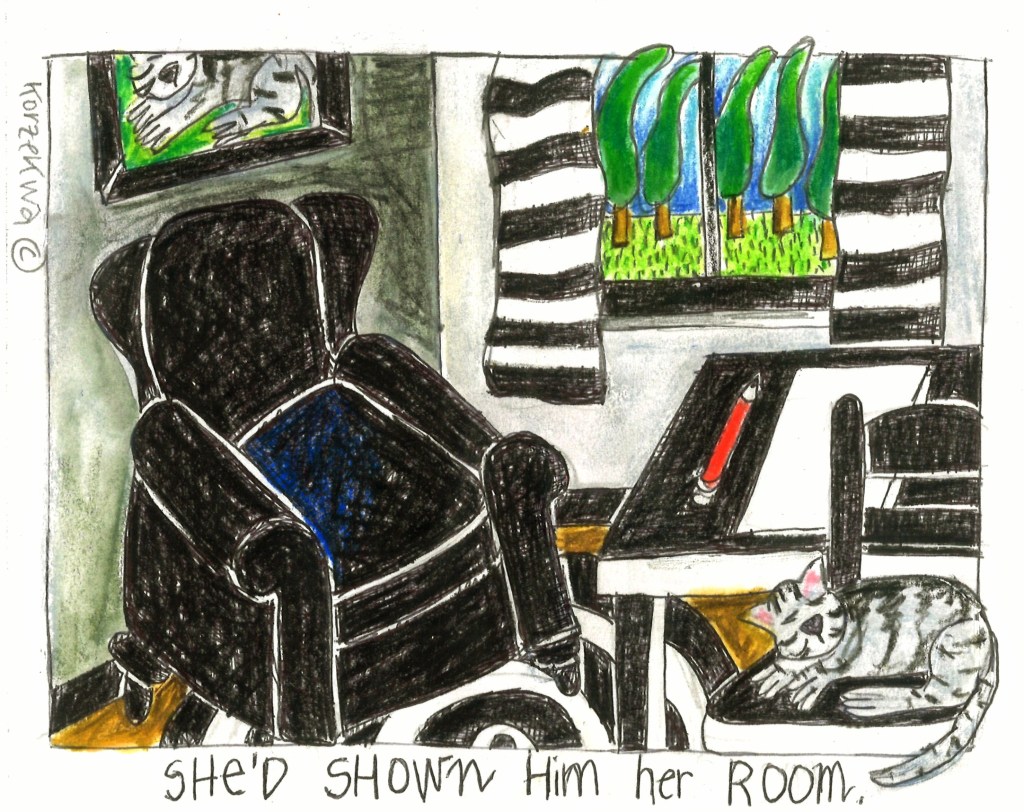

It’s easy to see that Citati was taken with Cristina’s physical presence and the aura she created. She was ephemeral and elusive, intriguing qualities for a man. Citati describes being invited to the room where she was staying in Rome and how Cristina took care to show Citati her elegant furniture, the small worktable, and an 1800s armchair. Everything about the room suggested cleanliness, precision, and asceticism. Cristina asked Citati if her room didn’t remind him of Emily, presumably Bronte.

To better understand Cristina and her poetry, it’s important to know that she was born with a heart defect that made demands on her daily life. Her fragile health kept her from attending a regular school. She studied alone and in isolation. Cristina used her solitude to translate authors like Katherine Mansfield, Virgina Woolf, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Simone Weil. Translating von Hofmannsthal and Weil had a profound effect on Cristina’s psyche and spiritual evolution.

Cristina’s real name was Vittoria Maria Guerrini. Her father, Guido, despite his love of music, was a committed fascist who used politics for social and economic mobility. When Mussolini fell, so did he. When German officers took over the convent in Fiesole where Cristina was living with her family, Guido, instead of being irritated by their presence, enjoyed having long conversations with them. Meaanwhile, Cristina worked for the Germans as a translator.

In 1944, British troops liberated Florence. Guido was arrested as a fascist and sent to a prison camp. But once freed, he easily rebuilt his career.

Cristina, a devout Catholic, never hid her fascist connection. Nor did she hide her fear of democracy. Maybe because there’s no such thing as democracy in religion.

In 1955, Cristina moved to Rome, a transition that had a tremendous effect on both her literary and spiritual evolution. For one, she began publishing her poetry and writing scripts for the RAI, Italy’s national radio and TV. And it was in Rome that she met Elèmire Zolla (1926-2002), writer, philosopher, and connoisseur of esoteric doctrines. Zolla’s marriage to the poetessa Mary Luisa Spaziani had recently ended.

Zolla introduced Cristina to mystical thought and esoteric doctrines. He also introduced her to Eastern religions including Zen and Hinduism. He took advantage of Cristina’s enthusiasm for the spiritual to help him write “I mistici dell’ Occidente” (the mystics of the west). And although Zolla was not a card-carrying fascist, his ideas easily aligned with far right and neo-Nazi philosophy. Julius Evola, a right wing intellectual and founder of esoteric fascism, was one of Zolla’s close friends.

Inside Cristina is an obsession. She burns her religion of form as if on a sacrificial pyre, says Citati. And she uses poetry to express this obsession.

I like the idea of poetry more than poetry itself. Their hermetically sealed meanings alienate me. How can you appreciate something you don’t understand. But let’s take a look at Cristina’s poem “Passo d’Addio” (Farewell Stop):

“neve era sospesa tra la

Notte e le strade

Come il destino tra la mano e il fiore.”

that roughly translated as:

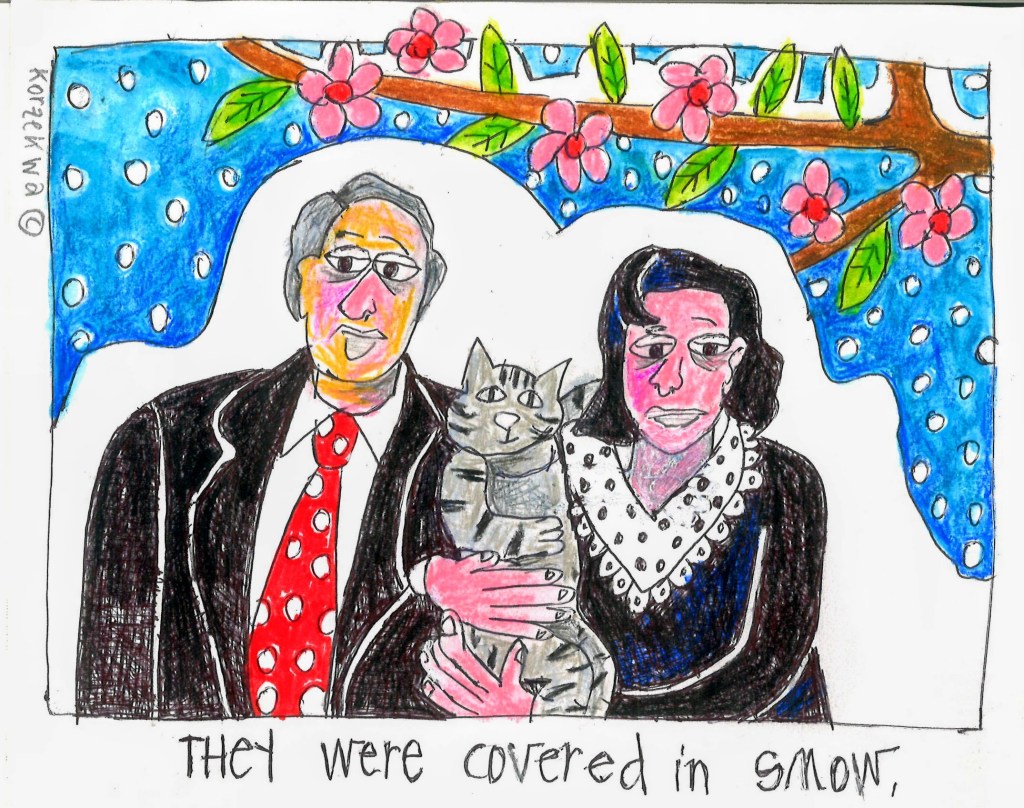

“the snow hung between

The night and the streets

Like a destiny between the

Hand and the flower.”

To read the entire poem (in Italian), go HERE.

Some scholars have interpreted the poem as being about a soul choosing to leave the limitations of worldly experience and human attachment to embark on a solitary and difficult path toward union with the divine. Cristina’s fragile health undoubtably influenced how she perceived life as something ephemeral. And if she was going to die early, she had to prepare her soul for departure.

Cristina hated the Vatican’s liberal reforms and was an activist for the reintroduction of the Latin liturgy. In post-war Florence, she enjoyed publicly praising Mussolini to passersby. Cristina was not at all progressive and detested anything that was modern. She considered the world an ugly place and thus had to look for meaning elsewhere. Such as in fairy tales and religion. Cristina, tormented by existential question, was restless within. And this often makes her sound too self-righteous and condescending.

Cristina could write about historic literature such as Shakespeare and Doctor Zhivago. But she also enjoyed writing about flying carpets and the religious practice of eating God to achieve communion (theophagy).

Cristina’s precarious health had simultaneously frightened and conditioned her. She’d chosen to live with her parents to feel more secure. But after the death of her parents, Cristina was so overwhelmed that she left the family home and moved into an apartment nest to the Benedictine Abbey of Sant’ Anselmo in Rome. She lived there until a heart attack ended her life. She was only 53.

Zolla also lived in the same apartment building as Cristina (#3 via Sant’ Anselmo near the Piazza Dei Cavalieri di Malta). In 1970, Zolla wrote the preface to the Italian edition of “The Lord of the Rings”. He portrayed Tolkien as a critic of modern chaos who used fantasy to arrive at the sacred. Zolla’s introduction to Lord was written in such a way that the neo-fascists easily identified with it. Even today, many right-wing politicians are Lord of the Rings fans. Even Italy’s prime minister is a devotee of Middle Earth and interweaves that fantasy in with Italian reality.

Tolkien was not at all pleased with his book being used as some kind of Nazi bible. Some claimed that the problem was, in part, the way the book was translated. But probably what was most alluring about Tolkien’s book was that it emphasized traditionalism, a quality very important for the right as it was for Cristina Campo.

-30-

Appropriations for AI will be jinxed.

Related:

Pietro Citati Wikipedia + Citati: “Lessi i Promessi Sposi a Gadda sul suo letto di morte” +

‘The Unforgivable’ and Other Writings by Cristina Campo + Two Faces of Catholic Traditionalism + Cristina Campo e le infinite corrispondenze + Cristina Campo ed Elémire Zolla: mistica e spiritualità nella svolta religiosa dei primi anni Sessanta via cristinacampo.it + Cristina Campo by Jaspreet Singh Boparai + The intransigence of grace. In memory of Cristina Campo, one hundred years after her birth +

Zolla: How The Lord of the Rings became a symbol for Italy’s far-right + Italian Anthroposophists and the Fascist Racial Laws + Prefazione di Elémire Zolla a Il Signore degli Anelli di J.R.R. Tolkien + Elémire Zolla, avversari metafisici nell’orbita del Kitsch +

Mario Luzi e Cristina Campo +