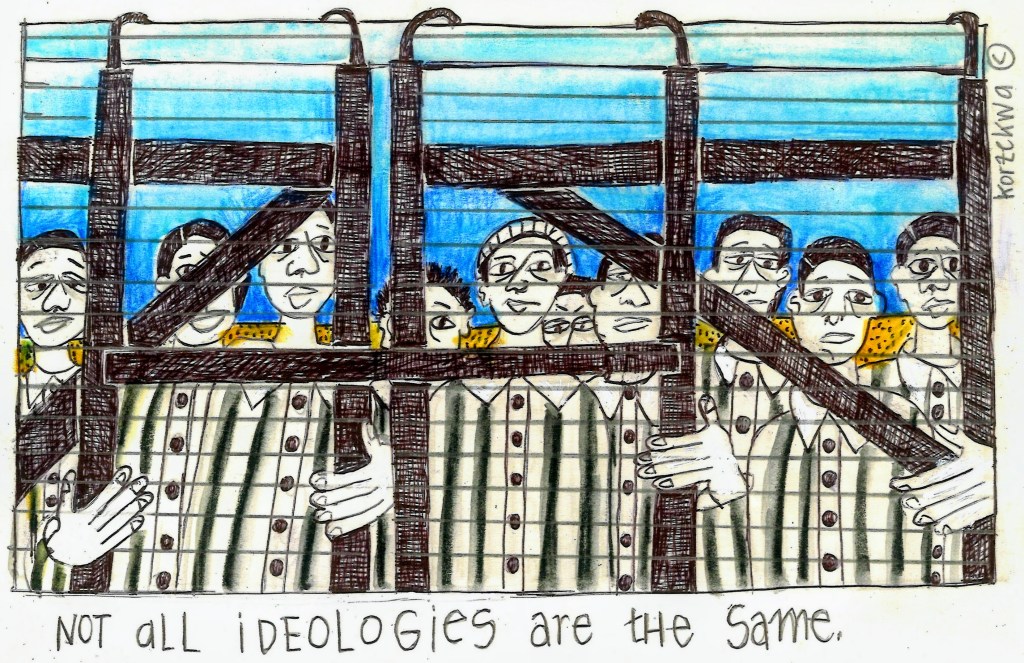

Fascism is on the rise. To better understand why, I feel the need to reflect on the fascism that led to WWII.

Fascism is the belief that we are not all equal. That there are those who impose. Then there are those who are imposed upon. As a woman, I am in the category of “imposed upon”.

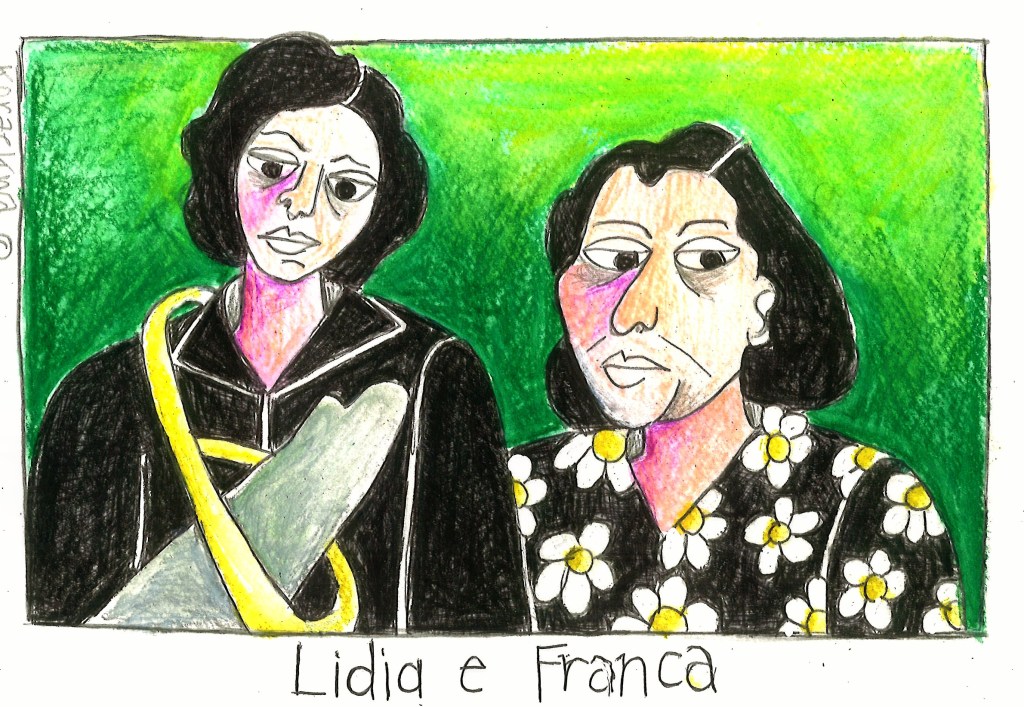

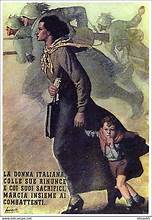

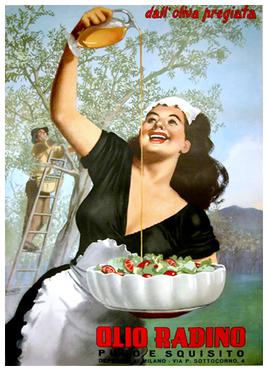

At the turn of the century, while other parts of the world were experiencing new approaches to women’s emancipation, Italian fascists were doing their best to restrict women from deciding for themselves. Fascists (males, of course) were deciding how women were to take care of their bodies, what they should study, what kind of participation in politics they could have, what their obligations to the regime were and blah blah blah. Fascists may have believed in progress for the state, but not for women. Women, they believed, were only there to serve their cause.

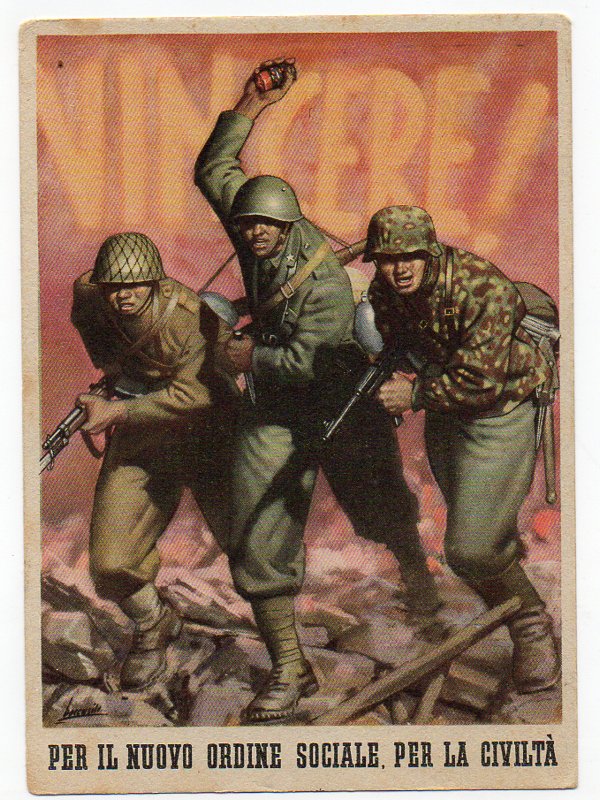

Mussolini came into power with his March on Rome in October of 1922. Hitler came into power in January 1933, 11 years after Benito. In fact, Hitler had been inspired by Mussolini. But once Hitler gained power, Mussolini’s role was radically transformed from prophet to acolyte. Why was this?

It was Hitler who first sought out Benito because Benito was considered the guru of fascism. Initially, Mussolini was not impressed by this attention. But, after the Nazis’ triumph in the 1933 elections, Mussolini took another look at his northern neighbor.

Although Mussolini had been the original mentor, that changed when he tried to invade Greece from Albania. Unable to take control of the situation, Germany took over the Balkans and saved Italy from an embarrassing defeat. That’s when Hitler decided he was the alpha man who could get things done and that Mussolini was only to follow his lead.

Fascist men all seem to suffer from the Macho Male Syndrome. If you’re male, you must be virile. And as proof of this virility, you need to be ruthless, competitive, angry, and incapable of properly expressing any emotion save for rage. Fascists see empathy not as a strength but as a weakness.

Fascists practiced Hegemonic Masculinity. That is, the sociocultural practice legitimizing men’s dominant position in society. A woman in fascist Italy asking herself “What are my perspectives?” would know full well that they were not the same as a man’s.

Italian priest and politician, Vincenzo Gioberti, expressed his thoughts on women like this: “Women are to men, somehow what the plant is to the animal or the parasitic plant to the one it latches to for sustenance.” In other words, women are like parasites. SOURCE

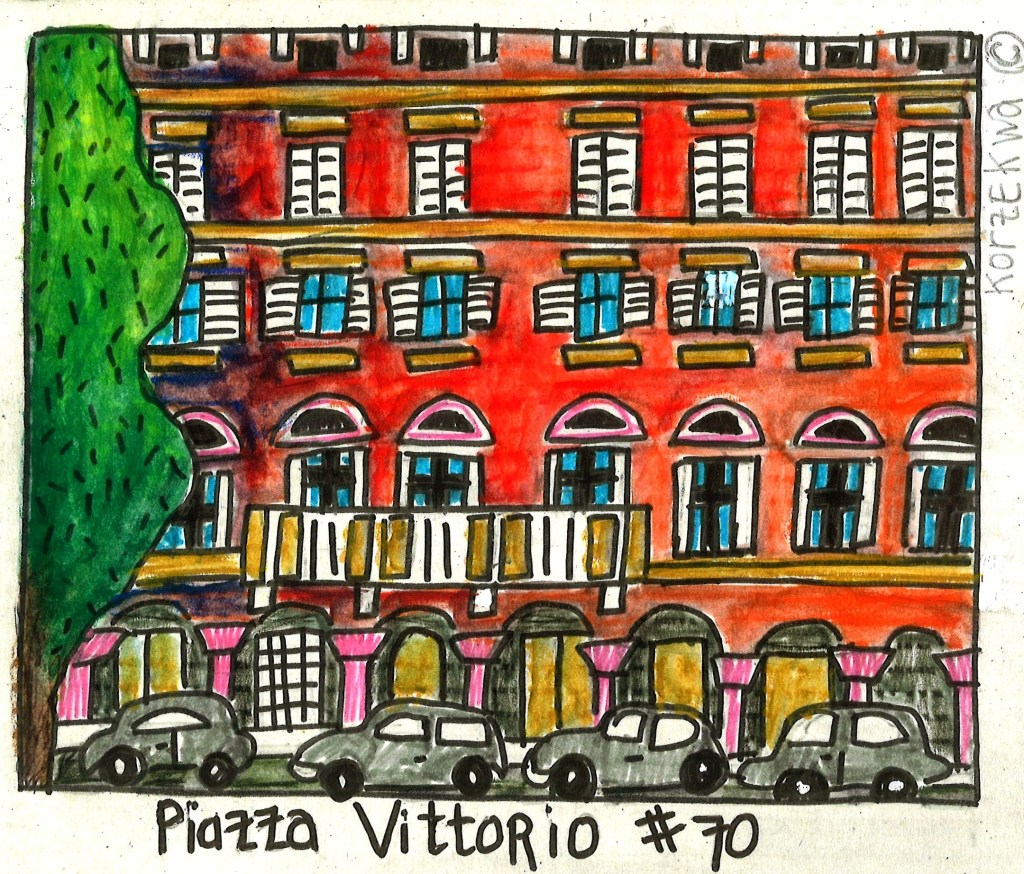

When Mussolini took over, Italy’s civil code was based on the Napoleonic code of 1806 established when the French occupied Rome. This code was the basis on which individual rights were established. It stated that: families were patriarchal, the father had the parental authority, only civil marriages were recognized, children born out of wedlock were cut out of an inheritance, adultery was a crime only for women, and etc.

For fascists, women’s primary role was to have babies as an increase in demographics was important for Mussolini’s goals. Mussolini needed soldiers, factory workers, and settlers for the African colonies. And women were expected to fulfill this need.

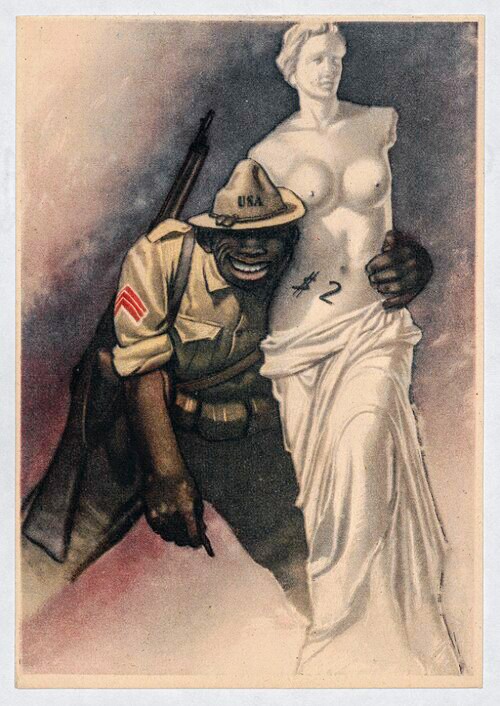

Italy and Germany, having arrived at unification only c. 1870, were in dire need of modernization to economically compete with other countries as industrialization in both Italy and Germany was way behind. Mussolini’s big dream was that of creating the New Roman Empire which meant geographical expansion. He invaded Africa and established the Italian Colonial Empire (1882-1960). The African colonies included Libya, Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

And, as we’ve seen, you need people to colonize someone else’s country.

In the early years of fascism, Mussolini seemed willing to concede more rights to women as there were many women’s groups pushing for it. But the willingness would morph periodically during the early years of fascism. However, in 1926, Mussolini banned all political parties and their propaganda. Why have elections if other choices have been obliterated? Why do you need the right to vote if there is no one to vote for?

Dictators do not emerge overnight.

Virility was publicly exalted whereas femininity was privatized and idealized. But this virility had to be on display and had to contribute to the cause. In 1927, a celibacy tax was imposed on all men between 25 and 65 of age who were not yet married. And, of course, homosexuality, which didn’t help the demographic cause, was a crime.

Despite the fascist preoccupation regarding wasted sperm, prostitution was permissable but only in state runned bordellos. The logic was that men were too virile not to fornicate all the time. Therefore, prostitutes were needed to pacify the macho within. Bordellos were also needed because the State worried about sexually transmitted diseases. By controlling the bordellos, women would be given routine medical checks. I don’t know how they dealt with unwanted pregnancies, though, as any kind of birth control as well as abortions were not permitted. Although there was some conflict between Fascists and the Catholic church (it’s always about power), the Church was complicit in keeping women in limbo.

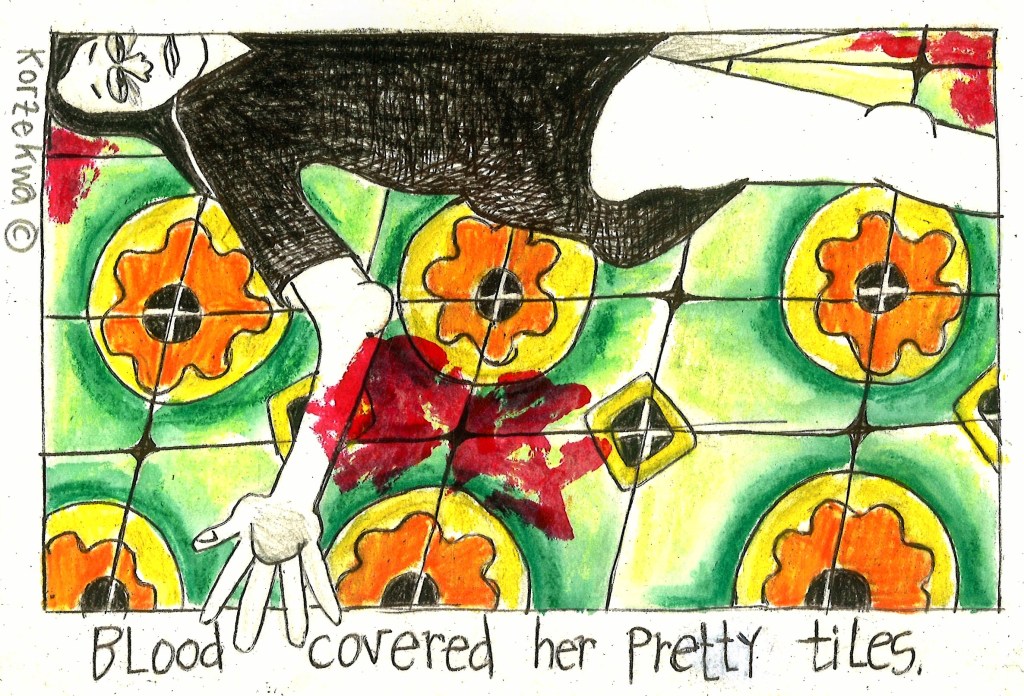

Patriarchy affects our health. Women and their emotions are minimized and/or completely dismissed causing a mutilation of women’s self-esteem. Domineering males and their gaslighting techniques undermine a woman’s authority. Men, acting like little roosters, need to crow all the time. Patriarchy is also why men feel the right to be both psychologically and physically abusive towards women.

Fascism discriminated against women. Discrimination has its consequences as seen in this excerpt from a previous post, The White Doll:

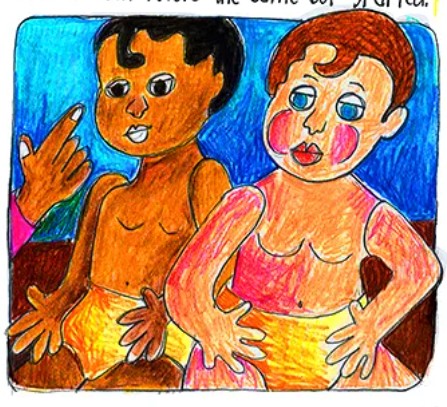

In the 1940s, psychologist Mamie Phipps Clark and her husband conducted a series of experiments known as the “Doll Tests”. The intent was to see the psychological effects of segregation on Black children.

Black children (ages 3-7) were presented with a white doll and a black doll then asked which doll was beautiful, which doll was good, which doll was ugly, and which doll was bad. The majority of the children indicated the white doll as good and beautiful whereas the black doll as bad and ugly. The psychologists concluded that discrimination and segregation had caused these children to feel inferior thus mutilating the perception they had of themselves.

Segregation subjected Blacks to a collective solitary confinement. Deprived interaction with the mainstream world, Black children grew up feeling isolated and inadequate. They considered themselves losers even before the game got started.

The results were so concrete and devastating that they were used in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional.

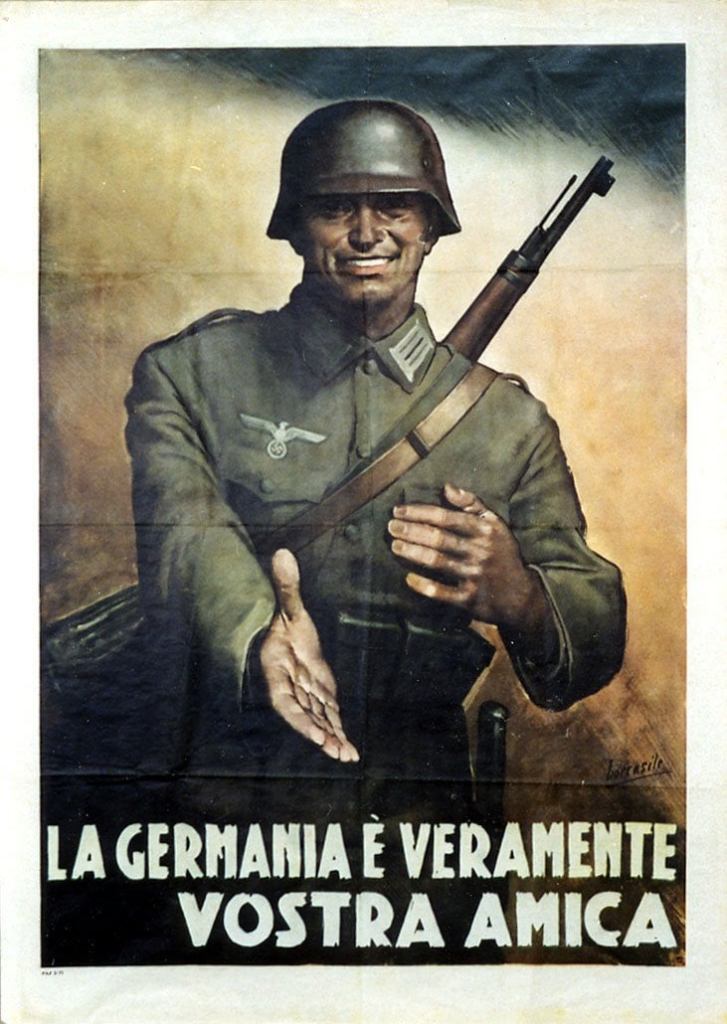

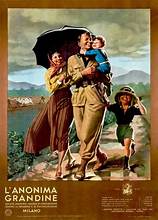

To accompany the text of this post, I’ve used posters by Gino Boccasile (1901-1952) as he was a major Mussolini supporter and provided many propaganda posters for the dictator. After the war, Boccasile was imprisoned for having collaborated with the fascists. His reputation damaged, he had difficulties finding work and supported himself by making pornographic drawings for publishing companies.

Although I have referred to various sources, the source of info mainly used here is from Victoria de Grazia’s “Storia delle donne nel regime fascista”. (How Fascism Ruled Women. Italy 1922-1945).

-30-

Appropriations for AI will be jinxed.

Bibliography:

de Grazia, Victoria. “Storia delle donne nel regime fascista”. (How Fascism Ruled Women. Italy 1922-1945). Marsilio Editori. Venezia. 2023.

Related:

History of Women’s emancipation in Italy + A History of Italian Citizenship Laws during the Era of the Monarchy (1861-1946) +

Celibacy Tax + The Deep Impact of Patriarchy: How It Influences Women’s Lives in Unseen Ways +