In 1776, the Declaration of Independence was signed proclaiming the emancipation of the 13 American colonies from Great Britain. But political independence does not automatically presume a cultural one.

America was indeed the land of plenty thus providing the opportunity to evolve economically. The number of nouveau riche grew and, with them, new needs. Of course, if you have money, you will want to, at some time or another, show it off. Huge mansions were built and well furnished. Only there was nothing to hang on the walls. The new country was so young that there had not been time to create a culture of its own. All they could do was to appropriate from their European roots. And, to do so, Americans needed to send young artists to Europe to copy important masterpieces. “High art” had to be imported. And assimilated.

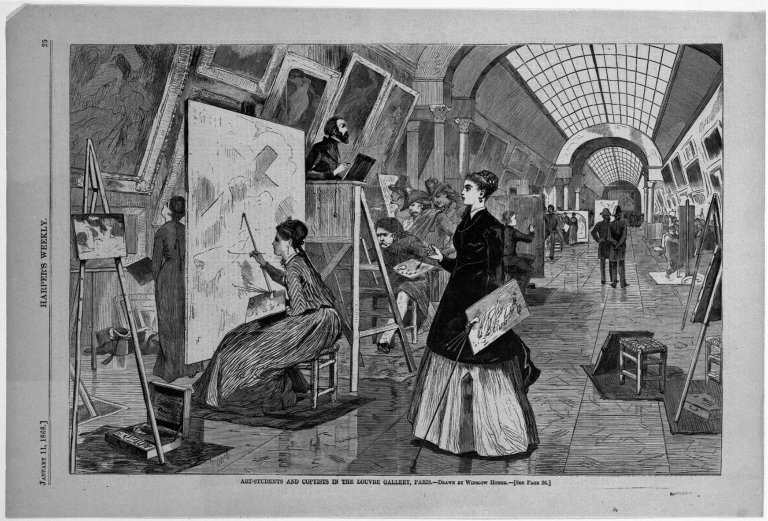

Copyists at the Louvre by Winslow Homer, 1868 via Archive

So young artists headed towards Europe to copy masterpieces. The highest concentration of art was in Rome thanks, in great part, to the Vatican. These artists were known as “copyists” because that’s what they did—copy. Women were considered perfect as copyists as they . could make affordable copies leaving the men to make the expensive originals.

By the mid-1800s, Rome had a large community of foreign artists living in Rome because it was cheap and had the biggest collection of art to copy.

Emma Conant Church (1831-1893) was the daughter of a Baptist minister and religious reformer. He believed in higher education for women. It was thanks to this reformistic view that Emma was given the freedom to study and to paint in Europe. Emma was one of the few working women artists before the Civil War.

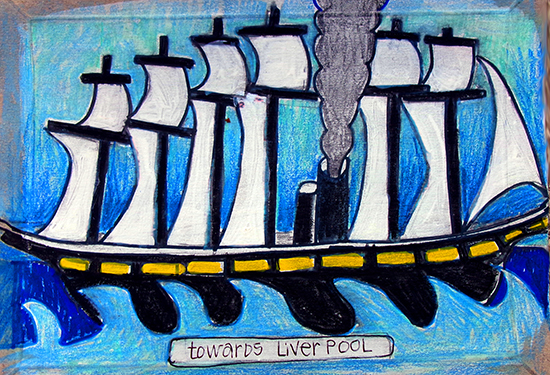

In 1860, Emma and her brother, a newspaper correspondent, docked in Liverpool having arrived on the Arabia steamship. They moved towards Paris where Emma immediately applied for the card that would give her permission to copy paintings at the Louvre. In 1861, even in Paris women were not allowed to attend art school. The ladies took private lessons if they could afford them. But since it opened, the Louvre was where artists went to learn about the Old Masters by copying them.

Copyists flooded galleries and museums and, with their easels in front of well-known paintings, they would spend so much time at museums that it is where they felt most at home. Copyists lived in museums during the day and in a garret at night.

At museums, people would observe them with curiosity. Often the presence of these ladies disturbed male visitors who were more accustomed to seeing women in passive roles and not as protagonists.

In 1862 Emma arrived in Rome. Italy was in the conflictual process of unification known as the Risorgimento. Nevertheless, for American visitors, Rome was cheap and accommodating. Emma achieved her greatest success in Rome. Although her family was not wealthy, in Rome, Emma was able to maintain herself.

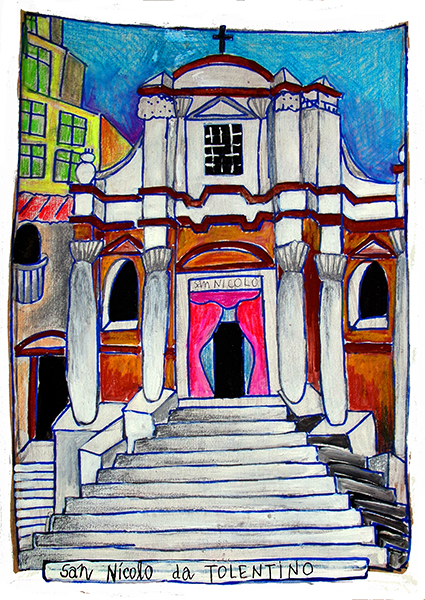

However, with the unification of Italy, things were radically. In 1867, Rome was in the middle of a revolution with nationalists pitted against French supported forces for control of the city. It seemed best for Emma to return to NYC where she opened a studio. She was successful but the poetics she’d felt in Rome were missing. In 1868, Emma returned to Rome and set up studio at via di San Nicola da Tolentino 68.

After the Risorgimento, it became more difficult for artists in Rome. The new political climate meant there were changes in the accessibility to the Vatican museums as well as to private collections. Many artists now opted for Paris and Rome’s cultural hegemony dwindled. Paris, under the direction of Napoleon III, was an exciting city in transition with Haussmann knocking down buildings to make room for boulevards and with the Impressionists creating new dynamics in the art world.

On his tour of Rome in 1862, Vassar College’s president, Milo P. Jewett, commissioned four copies from Emma including a copy of Guercino’s “The Incredulity of St. Thomas”. The following year Vassar College trustee, M. B. Anderson, was in Rome. After seeing copies of Emma’s paintings, he said that they’d been executed with “the most conscientious fidelity to the original and with the most complete success” and better than any other copies he’d seen. Everything was Zippity do Dah until Emma sent her bill to Vassar. They found Emma’s prices too high (didn’t they set a price before agreeing on the commission?). However, Emma was irritated, too. Generally, artists are paid half their commission from the beginning. But this hadn’t happened with her, and, as she had already paid the expenses involved with the painting including the framing, she needed to see some money. Eventually the artist and college reached an agreement as three of Emma’s paintings still belong to Vassar.

-30-

(Ekphrastic Copyists ©)

Related:

How America Became Rich, According to a Historian in 1802 +

Infesting the Galleries of Europe: The Copyist Emma Conant Church in Paris and Rome by Jacqueline Marie Musacchio + The case of Emma Church is a curious glimpse into the early history of Art at Vassar College +

Other ex-pats in Rome: Anne Brewster who wrote for American publications + Anne Whiteney, sculptor and poet + Abigail May Alcott Nieriker who studied in Rome with Frederic Crowninshield +

Pingback: Ekphrastic Copyists | The Narrative Within