Have you ever tried climbing the stairs of Montmartre wearing a long skirt? It’s so very stressful dragging meters and meters of fabric around wherever I go. For years I believed that skirts had no aesthetic merit as they impaired my ability to spontaneously interact with the world around me. Then I met Camille Doncieux.

J’adore Paris and its cafè chantants. Here no one cares if I drink too much wine then stand on my chair to sing. It’s in this context that I’ve met a number of artists (Impressionists in particular) and now frequently hang out with them. There’s nothing an Impressionist loves more than watching light jump around and there’s no better place to watch it jump than at a summer picnic, the kind where you spread out a big blanket so everyone can sit on it and act nonchalant. That’s why Impressionists have picnics all the time. And, as I had a particular talent for imitating les chanteurs de café, I‘m often invited to these picnics.

One such picnic was at Fontainebleau. That’s where I first saw Camille. She was sitting on the ground with her skirt spread out in front of her. The skirt didn’t signify confinement for her the way it did for me. To the contrary, she used all that fabric to establish her territorial domain and make her look like the captain of the ship. Her ship.

Camille had a small mouth, big eyes adorned by thick brows, and a great feel for fashion. When she met Monet, he immediately asked her to pose for him. She was only 18 and Monet seven years her senior. But some kind of chemistry was there as Camille continued to pose for him. And not only. She became his mistress. His parents did not approve of the relationship and so Monet kept it hidden so his father would continue to send him money. Camille got pregnant and the couple eventually married. But another pregnancy and years of living in poverty had weakened her. Camille got cancer and died at the age of 32. It was a hard blow for Monet. To ease the pain, Monet began an affair with Alice, wife of art collector fallen in disgrace Ernest Hoschedé. It was an awkward situation and made Alice emotionally insecure. So, like Pharaoh Akhenaton who had the name of the rival god Amon obliterated from Egyptian monuments, Alice tried obliterating the name of Camille whenever she could. But there wasn’t much Alice could do about all those paintings Monet had made of his first wife. She was haunted by those paintings of Camille with her skirt spread out in front of her as if to tell Monet “I am the subject matter and without me you are nothing.”

The years past and Monet matured as an artist. He gradually became disinterested in painting people and preferred, instead, to paint nature. In 1893, he bought a pond and decided to fill it with water lilies. And, like Erik Satie’s “Vexations” meant to be played over and over again, for the next 30 years, Monet painted over and over again water lilies. He didn’t want his paintings to look like his pond but, instead, wanted his pond to look like his paintings. “My finest masterpiece is my garden”, declared Monet.

Impressionism may have been French but Monet’s water lilies were not. He imported them from Egypt and South America. The local authorities were not happy. “Vive la France!” they said.

Ancient Egyptians were particularly fond of the cerulean blue lotus flowers. During the day the flower opens and extends its petals but at night it closes itself up again as if, symbolically, the soul can leave the body but then come back again.

Dried lotus leaves make an excellent tea conducive to lucid dreaming. It’s not known if Monet drank lotus flower tea but, as he matured artistically, his paintings became more and more abstract. Some critics implied that Money painted lilies because they were easy to paint. Others said that age had blurred his vision thus blurred his paintings.

It’s easy to understand Monet’s obsession with his pond. I don’t have a pond but I do have a balcony. And if I were to make paintings of my balcony plants, they would be mainly of yuccas. Only yuccas don’t inspire me to paint—all those pointed leaves, all that geometry.

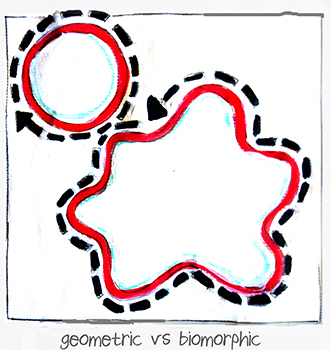

The time comes when you want biomorphic and not geometric shapes in your life. Geometric shapes like circles and squares are rigid and precise and boss you around. But biomorphic shapes are soft and irregular and easily flow. Geometric shapes make your eyes race whereas biomorphic shapes let them stroll. The older I get, the more biomorphic I become.

My relationship with shirts has greatly changed since first seeing Camille. I got rid of the cumbersome crinoline then took a course in drapage. There I learned how to drape the fabric on and around me in such a way as to force the eye to follow the folds. I knew when to pull the fabric tight and when to bunch it up to give myself a new contour. Draping gives my body a whole new interpretation. Thanks to my skirt, I can turn myself into a composition and throw a garden party without a garden.

(from Conditions of Possibility ©)

-30-

Bibliography:

Hidden in the Shadow of the Master: The Model-Wives of Cézanne, Monet, and Rodin by Ruth Butler (2008),

Your history lessons are simply wonderful.

And so are your comments!