Despite the drizzle, we walked to the Chinese restaurant to have lunch. Leaves that once hung over our heads were now matted on the ground—a melancholic reminder of existential change.

Despite the drizzle, we walked to the Chinese restaurant to have lunch. Leaves that once hung over our heads were now matted on the ground—a melancholic reminder of existential change.

Katherine Anne Porter was born in Texas in 1890. Her mother died when she was just a child and her father, overwhelmed, dumped his daughter on relatives. So it’s not surprising that Katherine did her best to run away from her childhood.

After an abusive marriage, a short career as an actress, and time spent in a sanatorium, Katherine began focusing on writing. In 1920, the magazine she was working with sent her to Mexico to cover the revolutionary movement. Here she became friends with Diego Rivera.

Katherine’s life in Mexico inspired some of her finest stories including that of “Flowering Judas”, a story about post-revolution Mexico. The protagonist is Laura, a gringa, who is in Mexico City teaching children English. She sees herself as someone who wants to help the downtrodden and gets involved with Marxist insurgents.

Laura is very attractive and has many suitors. One suitor is a 19 year old youth who comes on her patio one night and serenades her for a couple of hours. To get him to go away, Lupe, the housekeeper suggests that Laura throw him a blossom from the Judas tree which she does. The young man tucks the flower in his hat band, sings one more song, then goes away. But he continues to come back, follows her around, and leaves poems for her in the doorway.

Despite all of her politically related activities, Laura lacks commitment. Towards herself, towards her beliefs. One night Laura dreams she’s eating flowers from the Judas tree thus named because it’s the tree that supposedly Judas Iscariot hung himself from. Only in a dream does Laura acknowledge her self-betrayal, a betrayal that leads to feelings of isolation and alienation.

Moral: be true to yourself if you want to get a good night’s sleep.

The story of Laura is very similar to that of Katherine’s. They were both Roman Catholics, both young attractive women living in post revolution Mexico, both more at home when away from home. Both had difficulties anchoring themselves.

Katherine’s nephew, Paul, remembers her with great affection. Everything about her, he says, seemed glamourous. She liked to rouge her earlobes and wear long stings of pearls because she saw herself as a work of art. Katherine liked troubadour songs and writing in the margins of her books. She even tried correcting the Encyclopedia Britannica (as well as her cookbooks).

Katherine was a great conversationalist and loved to read poetry out loud. You could hear the punctuation when she spoke. She loved laughter and naughty jokes but, considering herself a Southern belle at heart, could never say obscenities.

Mary Queen of Scots and Joan of Arc were her role models. Katherine was an early riser, loved cats, and collected recipes. She made her own bread believing store bought bread was only for feeding pigeons. Having studied at the Cordon Bleu in Paris, she enjoyed sighing, kissing her fingertips, and rolling her eyes when talking about food.

Ship of Fools was the only novel she ever wrote. It was turned into a film offering her some economic security to maintain her eccentric lifestyle.

To read the essay about Katherine written by her nephew, see “Remembering Aunt Katherine” by Paul Porter in Katherine Anne Porter and Texas, An Uneasy Relationship, anthology ed. Machann & Clark (on Archive.org)

To read Katherine’s short stories, see The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter also on Archive.org.

Related: Springtime in Rome + Eudora Welty (1909-2001) + Ship of Fools film 1965 trailer + host James Day talks with writer Katherine Anne Porter about her nearly fifty year career youtube + SHIP OF FOOLS on Archive.org

It’s been raining every day now for about 10 days. The weather is becoming a serial psycho-killer. So I’m sitting here at the dining room table with the window curtains pulled back trying to squeeze in as much light as possible. Drawing with artificial light is just not the same as drawing with sunlight. I’m easily distracted and my mind jumps around looking for a place to land like a bee buzzes around looking for the right flower to suck. That’s how I got to Found Poetry.

There’s two basic ways of writing “found poetry”. The first is by copying phrases from books and mashing them up together to create a poem. You can further manipulate the existing text by deleting words and/or changing the punctuation. An excellent example of this type of found poetry is Annie Dillard’s “Mornings Like This: Found Poems”. Dillard has carefully recopied chosen sentence fragments from old and often forgotten books to create poems that are sometimes happy, sometimes sad. Below are a couple of excerpts from Dillard’s poems:

“Give me time enough in this place/And I will surely make a beautiful thing.” (from “Mornings Like This”)

“Think over what you have accomplished. Was it all that you wished? Has this story been told before?” (from “Junior High School English”)

(Annie Dillard’s “Mornings Like This” can be found on Archive HERE.)

But I’m a scissors & paste kind of woman and like the idea of de-obsoleting unwanted books (computer manuals, kids’ textbooks, boring unread novels) by cutting them up and, collage style, writing “found poems.” You know, anonymous letter style. But that would mean cluttering up even more my dining room table. So I’ve come up with an alternative—to take snippets of Dillard’s poems online and then evidence the words I want to keep and obliterate the others. Then they would be Found Poems Found within Found Poems.

Some examples:

-30-

Françoise Gilot was only 21 years old when she began her 10 year relationship with Picasso, then 61.

Was it Dumas who said that if a woman were to know at 20 what she knows at 40, she would live her life differently? Luckily for her, Françoise didn’t have to wait 10 more years to realize that, if she didn’t leave Picasso, he would devour her. But she did wait those 10 years to write about their relationship in “Life with Picasso” (1964).

Picasso may have been artistically rich but, emotionally, he was poverty stricken. Being in a relationship with him was risky. Wife Olga Khokhlova and lover Dora Maar were left psychology destroyed whereas lover Marie-Thérèse Walter and wife Jacqueline Roque committed suicide. Only Françoise escaped tragedy. Then again, what can you expect from a man who says “For me, there are only two kinds of women—goddesses and doormats.” And, if Picasso found a woman who was a goddess, he did his best to turn her into a doormat.

Picasso’s ego had him criticize other artists non-stop (for example, he called Braque “Madame Picasso”). He highly criticized Pierre Bonnard saying that he wasn’t a modern painter because Bonnard obeyed nature instead of trying to transcend it and that his paintings were a potpourri of indecision. Painting, said Picasso, was a matter of taking power. I, personally, adore Bonnard’s paintings. Maybe the real problem was that Bonnard lived with his wife (and model) from 1893 until her death in 1942. To commit oneself emotionally is a power Picasso didn’t have.

Despite his success as a seducer, Picasso for me is not sexy—how can there be anything sexy about a man who likes to blow a bugle but doesn’t like to dance.

As for Françoise, she is destined to have Picasso’s eternal shadow on her life. Like Marianne Faithful who will always be known for her relationship with Mick Jagger, Françoise will be known primarily for her relationship with Picasso. Of course she protests this saying that she should be considered his equal as “lions mate with lions. They don’t mate with mice.”

To read Françoise’s book free online see: “Life with Picasso”

-30-

“The Guersney Literary Club and Potato Peel Society” is a book about the bonding powers of letters and books. The story: writer Juliet Ashton is contacted by Dawsey Adams of The Guersney Literary Club and Potato Peel Society asking for information about the author Charles Lamb. This marks the beginning of an exchange of letters between Juliet and other members of the Literary Club.

The club began during the German occupation of Guersney Island. Tragically, one of its members, Elizabeth, was sent to Ravensbruck where she was executed. Juliet would like to write about Elizabeth as well as the experiences of other members of the group during the occupation.

The book is about how people and books can help one survive even the most difficult of situations.

The author, Mary Ann Shaffer, was an American librarian and editor who’d been encouraged by members of her writing group to write a novel even though she was already in her late 60s.

Mary Ann had difficulties in being consistent with her writing. So her group often tried nagging her into action. To explain her inertia, she once wrote them a letter.

Her story, she wrote, was about “a group of unlikely friends who are thrown together because of the exigency of living under the German Occupation during World War II.” But Mary Ann was having problems creating characters she liked. Of the characters she’d created, “there is not one of them I have any desire to spend time with,” she wrote.

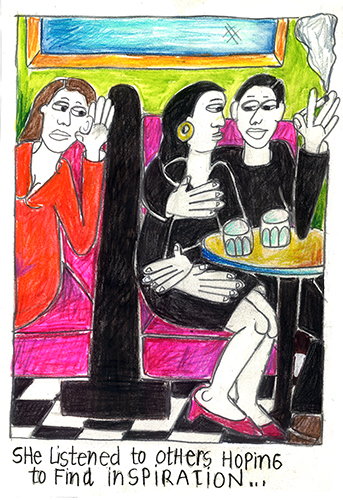

Since the book was based on letters, she tried developing characters by writing imaginary letters from them. But all the letters sounded alike. So she sought illumination from writing gurus who suggested going around eavesdropping on people then writing down what they said in little notebooks. But the people she listened to all sounded alike as well. She also read Annie Lamott who said that every character must have a unique passion. But on the island of Guernsey during the German Occupation, everyone had the same passion—finding food.

In the end, we are all alike.

“The Guersney Literary Club and Potato Peel Society” was published posthumously, a few months after Mary Ann’s death. It was the only book Mary Ann ever published. Pity she wasn’t around to see that it was a bestseller and transformed into a successful film.

“The Guersney Literary Club and Potato Peel Society” by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows is available on Archive HERE.

-30-