It was a beautiful day and had to be celebrated. So we got all dressed up then sat on a bench at κατω γιαλος (kato yialos) facing the sea. Sitting in front of a horizon line somehow expands the mind. Once expanded, we took a selfie before going to eat fresh fish at a favorite tavern.

Selfies and Sun

Self-Portrait with Hat

The day of her birthday, her thoughts were stronger than mirrors. “The future is now”, she told herself, “and I must focus on the present before it runs out.”

Birthdays made her think of musical arrangements. The song is the same but the way it’s interpreted can give it a whole new significance.

Saved by Stories

It was 947 AD and the camels were tired. We’d just gotten into Baghdad, my first time. Hugh, infatuated with the Silk Road, had insisted on traveling with the merchants to learn more about how cultures interrelate one with the other.

To travel with Hugh, I’d been obligated to dress like a man. Now all I wanted was a bath and to wear my own clothes again so I quickly headed towards the hammam at the woman’s quarters.

Life in a harem was a new experience for me. The quarters I‘d been assigned to were big and airy. The floors were covered with Antiochene rugs and cushions made from Damascene brocade. The mashrabiyas windows casted suggestive shadows on a water fountain adorned by qashani tiles. Everything was so enchantingly exotic. Save for the women. I’d expected to see them languidly laying around fanning themselves and eating dates. Instead, they were huddled together with their shoulders slumped and their eyes puffed up like muffins. Why was everyone so sad? As if reading my thoughts, a woman with hypnotic eyes came up to me. She introduced herself as Scheherazade and explained why the women looked so jaded.

King Shahrayar, cuckolded by his wife, had exorcized his wrath by killing her. But the anger wouldn’t go away so, like an authorized serial killer, every night he would share his bed with a young woman then have her executed the next morning. Now women were constantly fearing for their lives.

But Scheherazade, feminist and activist, along with her sister, Dunyazad, had come up with a plan. Scheherazade would volunteer to spend the night with Shahrayar but, before retiring to bed, would begin telling him a story that teased his imagination. Just as the story was about to reach a climax, she’d stop. The king, unable to confront a cliffhanger, would postpone killing her until the following night just to hear the story’s ending. The next night Scheherazade would finish quickly the story of the previous night but immediately would begin another one and, again, stop the story just as it was about to reach its climax. This, according to the plan, would go on indefinitely saving not only Scheherazade’s life but, above all, the lives of many other women as well.

“But how will you be able to come up with all these stories?” I asked. “By appropriation” she replied, “we will simply collect the stories that the merchants tell to entertain themselves while travelling on the Silk Road. Then we will rewrite them adding The Female Touch.”

For the next few days, we women of the harem busily collected stories. Finally we had 1000 tales and, after a lunch of saffron scented pilaf and fig balls rolled in sesame seeds, sat down to re-write them. Scheherazade, a scholar, knew that the Hindi used fairytales as medicine for emotionally unbalanced people.

There are emotions inside of us that we can’t escape. But standardized thinking patterns make it difficult to find solutions. That’s why imagination is necessary as it gives us the possibility to resolve conflict in various ways. Thus an emotionally sick person can contemplate on a fairytale then re-interpret it in such a way as to find his own solution. So why not heal King Shahryar in the same way.

The King’s main problem was that his psyche couldn’t let go of his wife’s unfaithfulness and, unconsciously, this lead him to believe that no one woman could ever truly love him. Thus all women were to be hated—and killed.

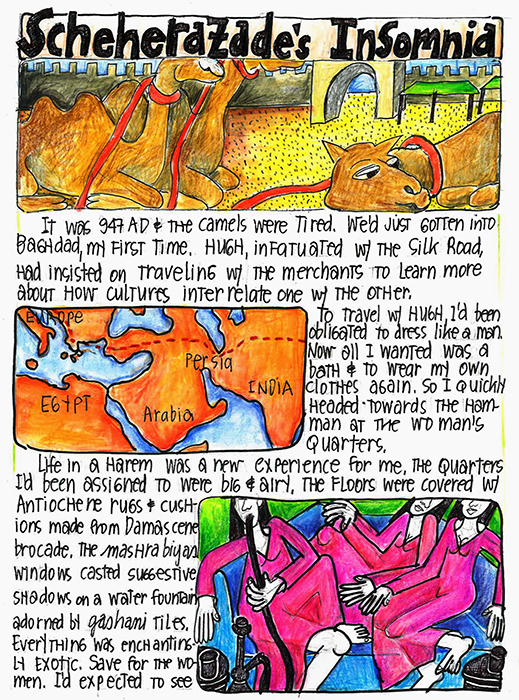

Knowing how well men loved them, Scheherazade would tell the king adventure stories but with carefully planted subliminal messages. For example, the story of Ali Baba on the surface is just another story about bandits. But in the end, it’s a story about the dangers of greed and the wonders of gratitude. The only men in the story who have a happy ending are those able to express gratitude towards Morgiana, the slave who saved Ali Baba’s life. Men and women, rather than compete, should enhance one another.

Storyteller and femme fatale, Scheherazade’s turn to spend the night with the king had arrived. Her silk skirt danced when she walked and her agarwood perfume left a trail two meters wide. That night the women of the harem stayed awake praying to the stars that Scheherazade’s life would be saved. And the next morning when she returned to our quarters, our sighs of relief and our joyful laughter could be heard around the world. Synergy and solidarity had brought us success.

For weeks, every night while Scheherazade was busy telling the king one story, the rest of us were busy preparing another one. And every morning when she returned alive, we danced to celebrate the lives that had been spared.

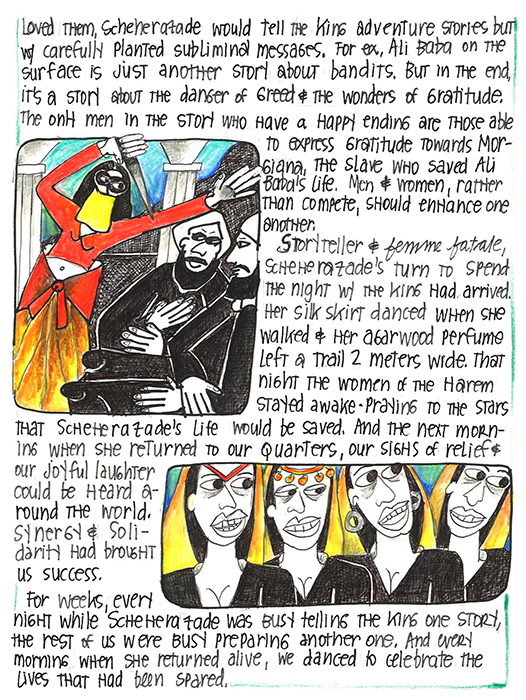

By this time I felt so much a part of the harem that I was a bit disappointed when, a few months later, Hugh, restless, wanted to go back to Rome so he could concentrate on his studies.

Once in Rome, life got back to normal and our experience of Baghdad and the Silk Road was slowly covered in dust. Several years later I learned that Scheherazade was not only alive and well after almost three years of storytelling, but she and the king had fallen in love. They were married and had three sons!

Stories can make things happen.

Stories are always based on a conflict to solve: a conflict with the self, a conflict with others, or a conflict with nature. And in between “Once upon a time” and “lived happily ever after” there’s a journey towards the self that must be taken in order to find a solution.

Dortchen Wild lived in Kassel and was part of the local women’s storytelling circle. She liked to tell stories like “Rumplestiltskin,” “”Hansel and Gretel”,” and “The Elves and the Shoemaker.” Some of the stories she’d heard from others, some she made up herself.

Napoleon’s troops had taken over the area of Kassel and two of Dortchen’s neighbors, Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, were afraid that local traditions and folk spirit were at risk. So they started collecting fairy tales and asked for Dortchen’s help. The brothers collected tales from other women as well such as Dorothea Vichmann who sold vegetables at the market (“The Three Feathers”, “The Goose Girl”) and the Hassenpflug sisters (related to the Grimm’s by marriage) also contributed to the fairy tale collection ( “Little Red Riding Hood”).

Now the problem was transforming oral stories into literary ones. In 1812, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published their first book of fairy tales. Although women had collaborated, the men got the credit.

Women, who enjoy communicating with others, are natural born storytellers. Storytelling was once a social event as well as means to pleasantly pass the time as they shared chores such as spinning, foraging, and child caring. Women’s stories were about the fears and desires of everyday life. And sometimes these stories silently left seeds in the subconscious to sprout at the most unexpected moment to offer a solution.

Self-narration.

Everyone has a story to tell. But often we don’t know how to recognize this story or, if we do, we don’t know how to tell it.

In Raymond Queneau’s best known work, Exercises in Style, the same story is told in 99 different ways: One day in Paris, the narrator gets on a bus and looks on as two men fight over space. The narrator later encounters one of these men at the train station getting advice as to how to sew a button onto his coat. Even if the story in itself is not very exciting, Queneau shows that there are limitless possibilities to affront the same situation.

Sometimes we have difficulties seeing ourselves as we really are because we’ve transformed self-interpretation into a cliché. But a fixed point of view can limit our options. Not all of us have Scheherazade’s talents. But we can still use stories to create personal change. A diary can help actualize this transformation.

Exercise: Write down the day’s events. Then retell the story in a different way. Like Queneau, explore the story until you find the narration that best suits you. Try turning a negative event into a Zen koan.

As narrator, you are the true protagonist.

(from Cool Breeze, aka The Age of Reconfiguration ©)

-30-

The Diary as Prayer

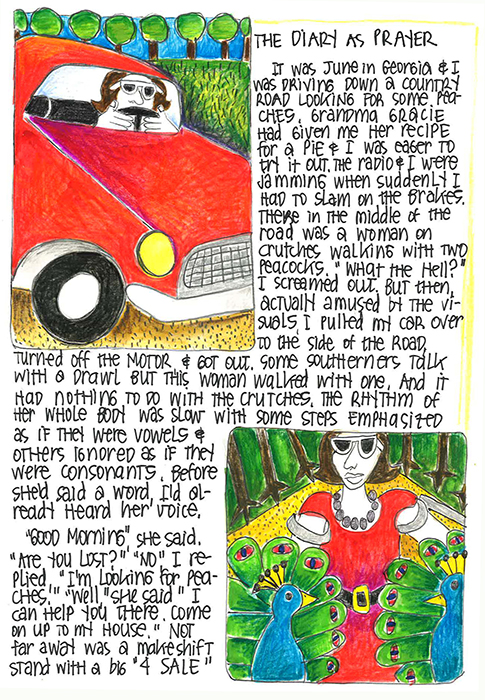

It was June in Georgia and I was driving down a country road looking for some peaches. Grandma Gracie had given me her recipe for a pie and I was eager to try it out. The radio and I were jamming when suddenly I had to slam on the brakes. There in the middle of the road was a woman on crutches walking with two peacocks. “What the hell?” I screamed out. But then, actually amused by the visuals, I pulled my car over to the side of the road, turned off the motor, and got out. Some southerners talk with a drawl but this woman walked with one. And it had nothing to do with the crutches. The rhythm of her whole body was slow with some steps emphasized as if they were vowels and others ignored as if they were consonants. Before she’d said a word, I’d already heard her voice.

“Good morning” she said “are you lost?” “No” I replied “I’m looking for peaches.” “Well” she said, “I can help you there. Come on up to my house.” Not far away was a makeshift stand with a big “4 Sale” sign in front of a basket of peaches. There were also Vidalia onions, pecans, and boiled peanuts in jars all in a row.

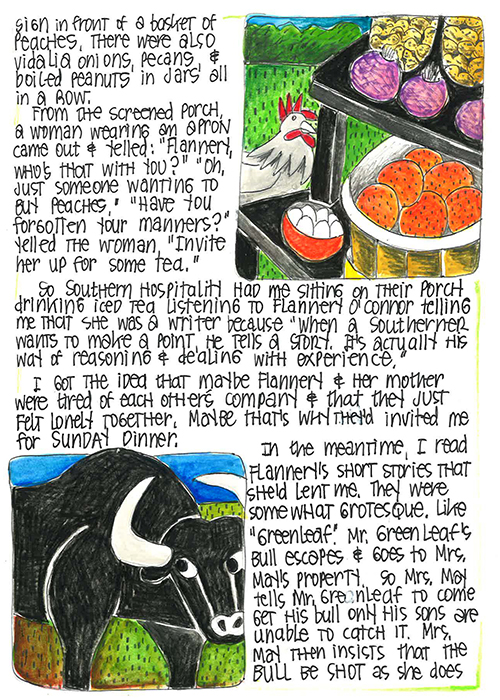

From the screened porch, a woman wearing an apron came out and yelled: “Flannery, who’s that with you?” “Oh, just someone wanting to buy peaches.” “Have you forgotten your manners?” yelled the woman, “Invite her up for some tea.”

So southern hospitality had me sitting on the porch drinking iced tea listening to Flannery telling me that she was a writer because “when a Southerner wants to make a point, he tells a story. It’s actually his way of reasoning and dealing with experience.”

I got the idea that maybe Flannery and her mother were so tired of each other’s company that it made them feel lonely. Maybe that’s why they invited me for Sunday dinner.

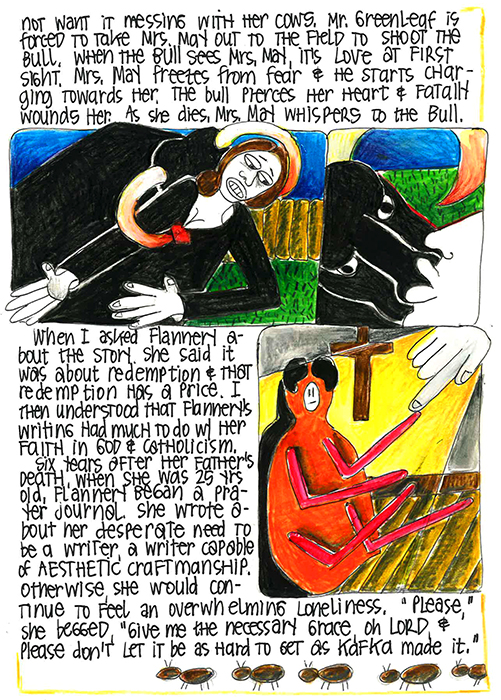

In the meantime I read Flannery’s short stories that she’d lent me. They were somewhat grotesque. Like “Greenleaf”. Mr. Greenleaf’s bull escapes and goes to Mrs. May’s property. So Mrs. May tells Greenleaf to come get his bull only his sons are unable to catch it. Mrs. May then insists that the bull be shot as she doesn’t want him messing with her cows. Greenleaf is forced to take Mrs. May out to the field to shoot the bull. When the bull sees Mrs. May, it’s love at first sight. Mrs. May freezes from fear and he starts charging towards her. The bull pierces her heart and fatally wounds her. As she dies, Mrs. May whispers to the bull.

When I asked Flannery about the story, she said it was about redemption and that redemption has a price. It hit me that Flannery wrote about her faith in God and Catholicism.

Six years after her father’s death, when she was 25, Flannery began a prayer journal. In this journal, she wrote about her desperate need to be a writer, a writer capable of aesthetic craftsmanship. Otherwise she would continue to feel an overwhelming loneliness. “Please,“ she begged, “give me the necessary grace, oh Lord, and please don’t let it be as hard to get as Kafka made it.”

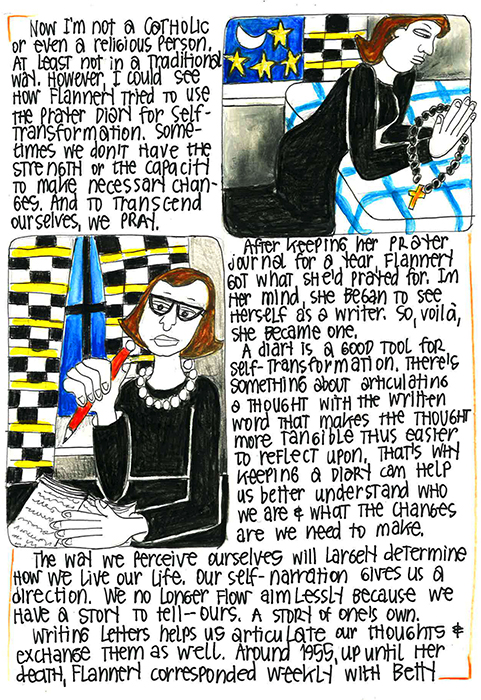

Now I’m not a Catholic or even a religious person, at least not in a traditional way. However, I could see how Flannery tried to use the prayer diary for self-transformation. Sometimes we don’t have the strength or the capacity to make necessary changes. And to transcend ourselves, we pray.

After keeping her prayer journal for a year, Flannery got what she’d prayed for. In her mind she began to perceive herself as a writer so, voilà, she became one.

A diary is a good tool for self-transformation. There’s something about articulating a thought with the written word that makes the thought more tangible thus easier to reflect upon. That’s why keeping a diary can help us better understand who we are and what the changes are we need to make.

The way we perceive ourselves will largely determine how we live our life. Our self-narration gives us a direction. We no longer flow aimlessly because we have a story to tell—ours, A Story of One’s Own.

Writing letters help us articulate our thoughts and exchange them as well. Around 1955 up until her death, Flannery corresponded weekly with Betty Hester, an Atlanta file clerk and a kind of literary groupie (Betty also corresponded with Iris Murdoch). Betty asked questions about theology and writing that forced Flannery’s mind to seek new roads. Just as coming up with the right questions forced Betty’s mind to seek new roads, too.

In 1951, Flannery was diagnosed with lupus, the same illness that killed her father. She died fourteen years later at the age of 39. Betty instead, shot herself in the head in 1998 at the age of 75.

In 1577, St. Teresa, the barefoot Carmelite and mystic who believed she’d been blessed with contemplation, wrote “The Interior Castle” as a guideline for those who sought prayer as a mystical union with God. Bernini obviously saw this union. His statue of her in Rome, known as the “Ecstasy of St. Teresa”, shows her about to be speared by an angel of God just as Mrs. May had been speared by a bull.

(from Cool Breeze, aka The Age of Reconfiguration ©)

-30-

Related: Whatever Happened to Pitty Sing?

Pain and Painting

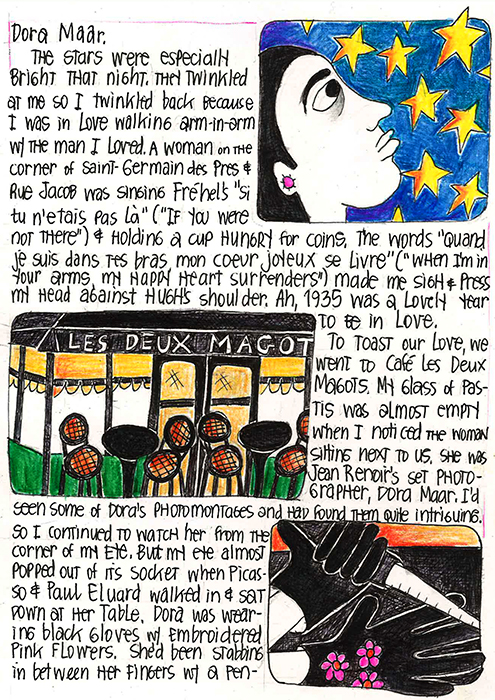

The stars were especially bright that night. They twinkled at me so I twinkled back because I was in love walking arm in arm with the man I loved. A woman on the corner of Saint-Germain des Pres and Rue Jacob was singing Fréhel’s “Si tu n’étais pas là” (“If you were not there”) and holding a cup hungry for coins. The words “Quand je suis dans tes bras, mon coeur joyeux se livre” (“When I’m in your arms, my happy heart surrenders”) made me sigh and press my head against Hugh’s shoulder. Ah, 1935 was a lovely year to be in love.

To toast our love we went to Café Les Deux Magots. My glass of pastis was almost empty when I noticed the woman sitting next to us. She was Jean Renoir’s set photographer, Dora Maar. I‘d seen some of Dora’s photomontages and had found them quite intriguing. So I continued to watch her from the corner of my eye. But my eye almost popped out of its socket when Picasso and Paul Eluard walked in and sat down at her table. Dora was wearing black gloves with embroidered pink flowers. She began stabbing in between her fingers with a pen-knife. Sometimes she’d miss causing blood to appear on her gloves. Picasso, who was blatantly fascinated, once Dora had stopped stabbing herself, asked for the gloves as a memento.

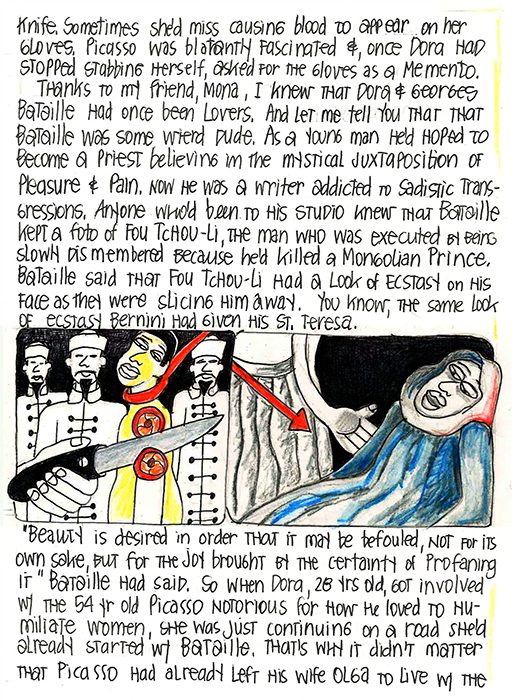

Thanks to my friend Mona, I knew that Dora and Georges Bataille had once been lovers. And let me tell you that that Bataille was some weird dude. As a young man he’d hoped to become a priest believing in the mystical juxtaposition of pleasure and pain. Now he was a writer addicted to sadistic transgressions. Anyone who’d been to his studio knew that Bataille kept a photo of Fou Tchou-Li, the man who was executed by being slowly dismembered to death because he killed a Mongolian prince. Bataille said that Fou Tchou-Li had a look of ecstasy on his face as they were slicing him away. You know, the same look of ecstasy Bernini gave his Saint Teresa.

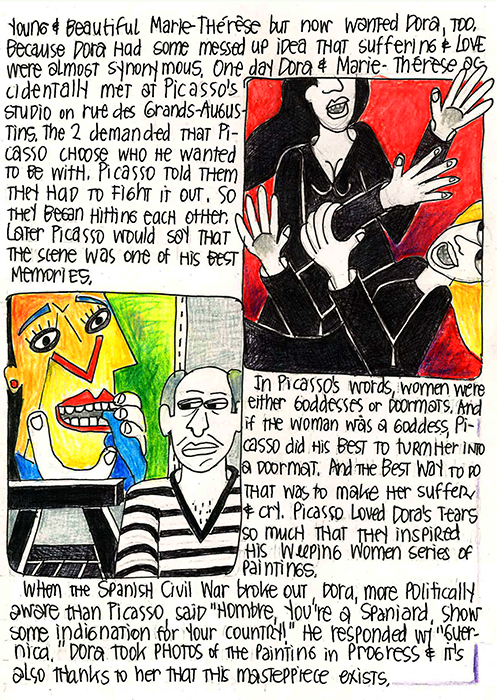

“Beauty is desired in order that it may be befouled, not for its own sake, but for the joy brought by the certainty of profaning it” Bataille had said. So when Dora, 28 years old, got involved with the 54 year old Picasso notorious for how he loved to humiliate women, she was just continuing on a road she’d already started with Bataille. That’s why it didn’t matter that Picasso had already left his wife Olga to live with the young and beautiful Marie-Therese but now wanted Dora, too. Because Dora had some messed up idea that suffering and love were almost synonymous. One day Dora and Marie-Therese accidentally met at Picasso’s studio on rue des Grands-Augustins. The two demanded that Picasso choose who he wanted to be with. Picasso told them they’d had to fight it out. So the women began hitting one another. Later Picasso would say the scene of them fighting for him was one of his best memories.

In Picasso’s words, women were either goddesses or doormats. And if the woman was a goddess, Picasso did his best to turn her into a doormat. And the best way to do that was to make her suffer and cry. Picasso loved Dora’s tears so much that they inspired him to paint a series of Weeping Women.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out, Dora, more politically aware than Picasso said “Hombre, you’re a Spaniard. Show some indignation for your country.” He responded with “Guernica”. Dora took photos of the painting in progress and it’s thanks to her that this masterpiece exists.

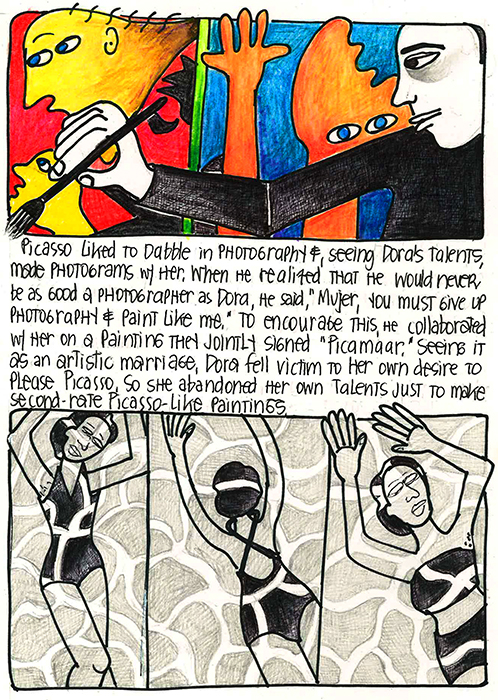

Picasso liked to dabble in photography and, seeing Dora’s talents, made photograms with her. When he realized that he would never be as good a photographer as Dora, he said, “Mujer, you must give up photography and paint like me”. To encourage this, he collaborated with her on a painting and they jointly signed “Picamaar”. Seeing it as an artistic marriage, Dora fell victim to her own desire to please Picasso. So she abandoned her own talents just to make second rate Picasso-like paintings.

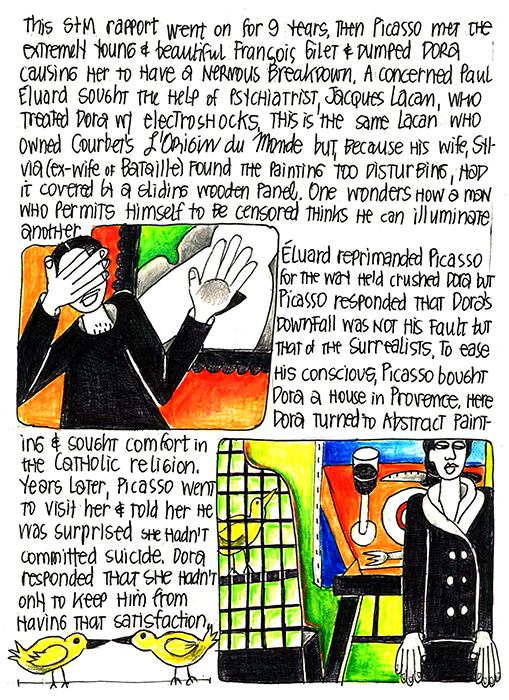

This S&M rapport went on for nine years. Then Picasso met the extremely young and beautiful Françoise Gilot and dumped Dora causing her to have a nervous breakdown. A concerned Paul Éluard sought the help of psychiatrist, Jacques Lacan, who treated Dora with electroshocks. This is the same Lacan who owned Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde but, because his wife Silvia (ex-wife of Bataille) found the painting too disturbing, had it covered by a sliding wooden panel. One wonders why a man who permits himself to be censored thinks he can illuminated another.

Éluard reprimanded Picasso for the way he’d crushed Dora but Picasso responded that Dora’s downfall was not his fault but that of the Surrealists. To ease his conscious, Picasso bought Dora a house in Provence. Here Dora turned to abstract painting and sought comfort in the Catholic religion. Years later, Picasso went to visit her and told her he was surprised she hadn’t committed suicide. Dora responded that she hadn’t only to keep him from having that satisfaction.

Misognynists.

Picasso hadn’t been totally wrong when he said that Dora’s downfall was the fault of the Surrealists. Despite their claims of being avant-garde, Surrealists were just as misogynist as conservatives.

Initially many women found Surrealism appealing because it was an alternative to a status quo that had never accepted them. Although never taken seriously as artists, Surrealism did give women the space to be introspective and self-referential.

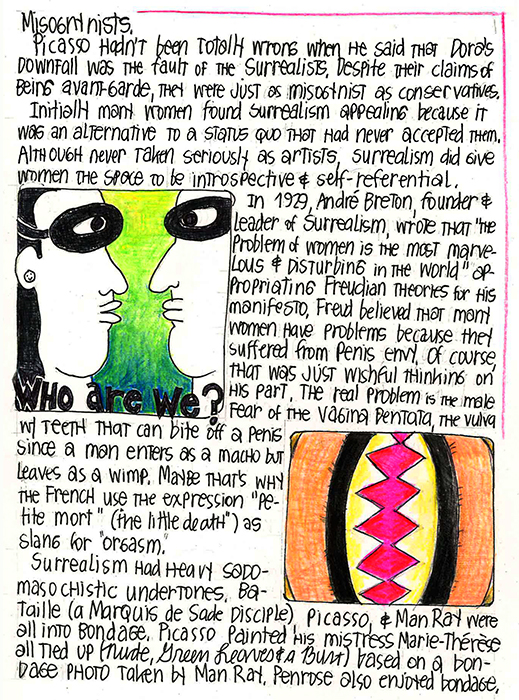

In 1929 André Breton, founder and leader of Surrealism, wrote that “the problem of women is the most marvelous and disturbing problem in the world” appropriating Freudian theories for his manifesto. Freud believed many women have problems because they suffered from penis envy. Of course, that was just wishful thinking on his part. The real problem is the male fear of the vagina dentata, the vulva with teeth that can bite off a penis since a man enters as a macho but leaves as a wimp. Maybe that’s why the French use the expression “petite mort” (“little death”) as a slang for orgasm.

Surrealism had heavy sadomasochistic undertones. Bataille (a Marquis de Sade disciple), Picasso, and Man Ray were all into bondage. Picasso painted his mistress Marie-Thérèse all tied up (Nude, Green Leaves and Bust) based on a bondage photo taken by Man Ray.

So why the need for men to tie up their women? It’s obviously about a power struggle. And women, brought up to feel guilty about having sexual desires, could appease this guilt if tied up and helpless.

After the horrors of WWII, Breton realized that his male oriented movement lacked a spirituality that, for biological reasons, only women possessed. Furthermore, women could no longer be considered the irrational sex as it had been men and not women who’d caused such a devastating and stupid war.

Lessons learned.

Beauty is ephemeral. If you base your life on your looks, you’re never going to be happy once you hit menopause.

Create your own identity and don’t let someone else try to do it for you. Never underestimate the value of your own self-esteem.

Just because you look good in a photo doesn’t mean you look good in real life.

In a patriarchal society, women will always be minimized next to a man.

Never love someone more than you love yourself. And, if you don’t know how to love yourself, it’s time you learned.

(from Cool Breeze, aka The Age of Reconfiguration ©)

-30-